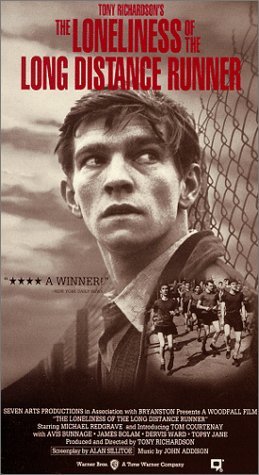

| The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Tony Richardson |

| Produced by | Tony Richardson |

| Written by | Alan Sillitoe |

| Starring | Tom Courtenay Michael Redgrave Avis Bunnage James Bolam Alec McCowen |

| Music by | John Addison |

| Cinematography | Walter Lassally |

| Edited by | Antony Gibbs |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films |

Release date | |

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £130,211[2] |

- Although the title of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner is drawn from the first and longest story in the collection, the nine stories are essentially independent, related only in the most.

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is a 1962 film based on the short story of the same name.The screenplay was, like the story, written by Alan Sillitoe.The film was directed by Tony Richardson, one of the new young directors emerging from documentary films, a series of 1950s filmmakers known as the Free Cinema movement. It tells the story of a rebellious youth (played.

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is a 1962 British coming-of-age film. The screenplay was written by Alan Sillitoe from his 1959 short story of the same title. The film was directed by Tony Richardson, one of the new young directors emerging from the English Stage Company at the Royal Court.

It tells the story of a rebellious youth (played by Tom Courtenay), sentenced to a borstal for burgling a bakery, who gains privileges in the institution through his prowess as a long-distance runner. During his solitary runs, reveries of important events before his incarceration lead him to re-evaluate his status as the prize athlete of the Governor (Michael Redgrave), eventually undertaking a rebellious act of personal autonomy and suffering an immediate loss of privileges. The film poster's byline is 'you can play it by rules... or you can play it by ear – WHAT COUNTS is that you play it right for you...'.[3] The notion is echoed by other contemporary films, such as a rapid series of three contemporary Lone Ranger films.

The film depicts Britain in the late 1950s and early 1960s as an elitist place, where upper-class people enjoy many privileges while lower-class people suffer a bleak life, and its Borstal system of delinquent youth detention centres as a way of putting working-class people in their place. Alan Sillitoe was one of the angry young men producing media vaunting or depicting the plight of rebellious youths. The film has characters entrenched in their social context. Class consciousness abounds throughout: the 'them' and 'us' notions that Richardson stresses reflect the basis of British society at the time, so that Redgrave's 'proper gentleman' of a Governor is in contrast to many of the young working-class inmates.

Sillitoe's story The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, which concerns the rebellion of a borstal boy with a talent for running, won the Hawthornden Prize in 1959. It was also adapted into a film, in 1962, directed by Tony Richardson and starring Tom Courtenay. Sillitoe again wrote the screenplay. With Fainlight he had a child, David.

Plot[edit]

The film opens with Colin Smith (Tom Courtenay) running, alone, along a bleak country road somewhere in rural England. In a brief voiceover, Colin tells us that running is the way his family has always coped with the world's troubles, but that in the end, the runner is always alone and cut off from spectators, left to deal with life on his own.

Colin is then shown with a group of other young men, all handcuffed. They are being taken to Ruxton Towers, a detention centre for juvenile offenders, an approved school. It is overseen by the Governor (Michael Redgrave), who believes that the hard work and discipline imposed on his charges will ultimately make them useful members of society. Colin, sullen and rebellious, immediately catches his eye as a test of his beliefs.

The boys live in a series of Nissen huts with no privacy.

An important part of the Governor's rehabilitation programme is athletics, and he soon notices that Colin is a talented runner, easily able to outrun Ruxton's reigning long-distance runner. The Governor was once a runner himself, and he is especially keen on Colin's abilities because, for the first time, his charges have been invited to compete in a five-mile cross-country run against Ranley, a nearby public school with privileged pupils from upper-class families. The Governor sees the invitation as an important way to demonstrate the success of his rehabilitation programme.

The Governor takes Colin under his wing, offering him outdoor gardening work and eventually the freedom of practice runs outside Ruxton's barbed-wire fences. This is shown interspersed with a series of flashbacks showing how Colin came to be incarcerated, beginning with one showing his family's difficult, poverty-stricken life in a lower-class district of industrial Nottingham, where they live in a prefab. The jobless Colin indulges in petty crime in the company of his best friend, Mike (James Bolam). Meanwhile, at home, his father's long years of toil in a local factory have resulted in a terminal illness for which he refuses treatment and dies, leaving Colin as the family’s jobless breadwinner.

Colin rebels by refusing a job offered to him at his father's factory. The company has paid a paltry £500 in insurance money, and he watches with disdain as his mother (Avis Bunnage) spends what Colin considers an offensive sum. Colin symbolically burns some of his portion of the insurance money and uses the rest to treat Mike and two girls they meet to an outing in Skegness, where Colin confesses to his date, Audrey (Topsy Jane) that she is the first woman he's ever had sex with.

His mother moves her lover, whom Colin resents, into the house; an argument ensues, and she tells Colin to leave until he can bring home some money. He and Mike take to the streets, and they spot an open window at the back of a bakery. There is nothing worth stealing except the cashbox, which contains about £70 (equivalent to £1,500 in 2019). Mike is all for another outing to Skegness with the girls, but Colin is more cautious and hides the money in a drainpipe outside his house. Soon the police call, accusing Colin of the robbery. He tells the surly detective (Dervis Ward) he knows nothing about it. The detective produces a search warrant on a subsequent visit, but finds nothing. Finally, frustrated and angry, he returns to say he'll be watching Colin. As the two stand at Colin's front door in the rain, the torrent of water pouring down the drainpipe dislodges the money, which washes out around Colin's feet.

This backstory is interspersed in flashbacks with Colin's present-time experiences at Ruxton Towers, where he must contend with the jealousy of his fellow inmates over the favouritism shown to him by the Governor—especially when the Governor decides not to discipline Colin, as he does the others, for rioting in the dining hall over Ruxton's poor food. Colin also witnesses the kind of treatment given to his fellows who are not so fortunate: beatings, bread-and-water diets, demeaning work in the machine shop or the kitchen.

Finally, the day of the five-mile race against Ranley arrives, and Colin quickly identifies Ranley's star runner, Gunthorpe (James Fox). The proud Governor looks on as the starting gun is fired. In the final mile Colin overtakes Gunthorpe while running through the woods and then gains a comfortable lead with a sure win, but a series of jarring images run through his mind: jumpcut flashes of his life at home and his mother's neglect; his father's dead body; stern lectures from detectives, police, the Governor and Audrey. Just yards from the finish line, he stops running and remains in place, despite the calls, howls and protests from the Ruxton Towers crowd. In close-up, Colin looks directly at the governor with a defiant smile, an expression that remains as the Ranley runner passes the finish line to victory. The Governor is clearly disappointed.

At the end, Colin is back in the Borstal's machine shop, now ignored by the Governor.

Cast[edit]

| Actor | Character |

|---|---|

| Michael Redgrave | Ruxton Towers Reformatory Governor |

| Tom Courtenay | Colin Smith |

| Avis Bunnage | Mrs Smith |

| Alec McCowen | Brown |

| James Bolam | Mike |

| Joe Robinson | Roach |

| Dervis Ward | Detective |

| Topsy Jane | Audrey |

| Raymond Dyer | Gordon, Mrs Smith's boyfriend |

| Julia Foster | Gladys |

| Arthur Mullard | Chief Borstal Officer (uncredited) |

| James Fox | Gunthorpe (uncredited) |

| John Thaw | Bosworth (uncredited) |

| Derek Fowlds | (uncredited) |

Production[edit]

Writing[edit]

Sillitoe's screenplay can be interpreted as either tragic or bathetic by ultimately projecting the protagonist as a working class rebel rather than an otherwise rehabilitated but conformist talent. During the period when Sillitoe wrote the book and screenplay the sport of running was changing.[4] The purity of running was taken away when Smith entered the race for his own and his institution's benefit — a commodity useful for his patrons' own promotion.[5][4] Sillitoe rejects the commoditisation of running in his book and screenplay, believing instead a professional becomes commercialised and loses the clarity of thought that comes with running otherwise.[6] This is why Smith chooses to forfeit the race. Literary critic Helen Small states, “…the weight of literary attention seems to be focused on a ‘pre-professional era’ — either written at that time or looking back at it for inspiration”.[4] Her research stresses that Sillitoe was an author who believed in the unadulterated sport.

Running is also used as a metaphor to give Smith the ability to escape from the reality of his class level in society.[5] The use of this sport gives Smith the ability to escape from his life as a member of the working class poor. Sillitoe has used running to give his character a chance to reflect upon his social status and also to escape from the reality that the poor in Britain are faced with.[5]Long-distance running gives the character an ability to freely escape from society without the pressures of a team, which may be found in other athletic stories.[5]

Filming[edit]

Locations were shot in and around Ruxley Towers, Claygate, Surrey – a Victorian mock castle built by Henry Foley, 5th Baron Foley. The building had been used by the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes during the Second World War.

Music[edit]

The original trumpet theme to the film was performed by Fred Muscroft, the Principal Cornet (at the time) of the Scots Guards.

Reception[edit]

The film holds a rating of 70% on Rotten Tomatoes from 23 reviews.[7]

Box office[edit]

The film was a box-office disappointment.[8]

Awards and nominations[edit]

- Most Promising New Actor - BAFTA (Tom Courtenay)

- Best Foreign Director (nominee) - Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists (Tony Richardson)

- Best Actor - Mar del Plata Film Festival (Tom Courtenay)

- A 2018 Time Out magazine poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers, and critics ranked it the 36th best British film ever made.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner on IMDb

- ^Petrie, Duncan James (2017). 'Bryanston Films : An Experiment in Cooperative Independent Production and Distribution'(PDF). Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television: 7. ISSN1465-3451.

- ^Poster, see wikimedia for further source information

- ^ abcSmall, Helen. 'The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner in Browning, Sillitoe and Murakami.' Essays in Criticism 60.2 (2010): 129–147. EbscoHOST.

- ^ abcdHutchings, William. “The Work of Play: Anger and the Expropriated Athletes of Alan Sillitoe and David Storey.” Modern Fiction Studies 33.1(1987): 35–47. EbscoHOST.

- ^Small, p 142.

- ^http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/loneliness_of_the_long_distance_runner

- ^Petrie p 14

- ^Calhoun, Dave; Huddleston, Tom; Jenkins, David; Adams, Derek; Andrew, Geoff; Davies, Adam Lee; Fairclough, Paul; Hammond, Wally (10 September 2018). 'The 100 best British films'. Time Out London. Time Out Group. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

External links[edit]

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner on IMDb

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner at Rotten Tomatoes

Slot Machine Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner Summary

Al Howie’s thick mustache and Scots brogue remain intact. He’s still lean and sinewy, not far off the 135 pounds he weighed in his prime 15 years ago, when he was the greatest ultramarathoner on Earth. But he’s 61 now and wears thick glasses, his vision hampered by diabetes, and his hands quiver. “I’m sorry I’m not in better shape,” he says quietly, in the Duncan group home where he lives today. “But I guess we all have our problems.”

Meeting him under these circumstances, it’s hard to believe he once held several Guinness world records – but then again, so many things about Al Howie’s life have been unlikely. Born in a tough port town near Glasgow, he spent all of his 20s as a vagabond hippie, got married twice, fathered two children, and didn’t start running until he was nearly 30 and living in Toronto, trying to work off the aggression from a quitting a three-pack-a-day smoking habit. After he moved to Vancouver Island with his son in 1978, his hobby became an obsession. He started entering races, and though he did well in marathons, he found that if he ran in even longer contests, he was always way out in front.

To finance his races, he worked as a tree planter; for a while he had a job at copper mine near Port Hardy and ran to and from work, 12 miles each way. On the racing circuit, he became famous as much for his unusual style as his victories. Wearing a “Tartan Spartan” T-shirt, helived on a steady diet of beer and fish and chips – sometimes even during a race. “It drove people crazy. They’d see me knocking back a beer while they were stretching, and the next time they’d see me would be up on the podium.” On top of that, to keep expenses down, he’d often run to races in other cities, putting his bags on the bus to a distant town, catching up to them and changing clothes, then sending them on to the next stop. He ran from a marathon in Edmonton to one in Victoria. He ran from B.C. to California for a race, and from England to Italy. And when he reached his destinations, he often won.

But after Howie was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1985 – which he claimed to cure by switching to a macrobiotic diet – he got serious, and set a series of astonishing long-distance records. At UVic in 1987 he jogged 580 km nonstop in 104.5 hours, the world’s longest continuous run. In 1988 he ran the 1,400-km length of Britain in 11 days. In 1989 he became the first person to finish the Sri Chinmoy 1,300-mile race in New York, beating its 18-day time limit. (That's Howie with the Bengali guru behind the race in the photo at top.) And on September 1, 1991, he arrived in Victoria, finishing the fastest-ever run across Canada, in 72 days – averaging 103 km, the equivalent of two-and-a-half marathons, every single day.

Why do it? “People walk long distances, and running’s more entertaining,” he replies bluntly. “You see more.” Plus there’s the satisfaction of setting a seemingly impossible goal, planning, focusing, and then achieving it. Howie’s never talked much about the zen of running, but he did once say his sport was a way of escaping from the materialism of everyday life, from “earning or spending, buying or selling.” “I’m in my element when I’m doing it,” he told a reporter in 1998. “All that matters is that you cover ground, eat right. You stop worrying about Saddam Hussein, or that the rent’s due back home.”

But the material world caught up with him. Though he loved talking to people while running, he never cashed in as a motivational speaker. Though he raised thousands of dollars for charities, he often lived in bitter poverty. As he wrote in a letter to Monday in 1987, during a round-trip run to the Queen Charlotte Islands for the United Way, “Sometimes I run on adrenalin .... more often, I run on resentment, angrily pounding the blacktop. Why must I run on empty? Why do I get no support from my hometown? Mostly, I plod on because I have committed myself to this asphalt insanity and I simply don’t know how to quit.”

His personal life has suffered too. He’s no longer with his third wife. He's lost contact with his daughter, who runs an NGO for disabled kids in Peru, and his son, who was deported back to Scotland after a marijuana arrest. In 1992 Howie realized he had Type 1 diabetes, and though he managed it carefully, in 2001 he suddenly lost his motivation to compete and started being treated for depression, a common condition for insulin-dependent diabetics. “The talent’s still there,” he says. “But I didn’t deserve quite that amount of bad luck.”

Near the end of this weekend’s Royal Victoria Marathon, runners will pass the statue of Terry Fox, and the sign for Fonyo Beach. But they’ll actually have to stop and look closely at Mile Zero to see the small plaque there commemorating Al Howie’s own incredible run across Canada. His other records have since been surpassed, but at least he gets some satisfaction knowing that one is literally set in stone. “I don’t think anyone’ll ever beat it,” he says, and he’s probably right.

UPDATE (December 4, 2007): Last night the City of Duncan presented Al with its annual Sports award, in recognition of his achievements. More than 100 people attended the ceremony. Congratulations, Al!